Following Morton: the 1990 introduction

This is the original 1990 introduction to the story of my van trip around England with sketchbooks and pencils.

[Bracketed sections are comments added in 2020.]

It was at a car-boot sale near Winchester School of Art one Sunday morning in 1989 that I first came upon a battered paperback edition of HV Morton's In Search of England. First published in 1927, it tells the idiosyncratic story of a man's looping journey around England in his bull-nosed Morris. Once I had it in my hands, the temptation to flick through its pages to find his reactions to places I knew was irresistible.

It is a book that has hardly been out of print since. Morton blended an informal, humorous style with an interest with history that brought the country's past within reach of anyone who wanted it. The growing popularity of the motor car was making the towns and countryside more accessible to the public than ever before. Within 14 years it was into its 27th edition.

Morton had an aim, one that his readers evidently shared with him, and that was to "find" England. He knew what he wanted and he set out to discover it. His journey was loaded with many of the views you may expect from a gentleman's tour in the time of the Empire, so much so that by the last page he is able to turn to a country parson and pompously tell him, "You have England."

[Pomposity was the least of Morton's many failings: you can find a bookful more in Michael Bartholomew's 2004 biography of him, titled In Search of HV Morton.]

But flicking through this paperback more than 60 years later, I wasn't so sure what the bombs and bulldozers had left to be found today. I had an idea that the "heritage industry" would have packaged much of what he had described into neat bundles of visitor centres, gift shops and theme parks set against a rising tide of satellite dishes and out of town shopping centres. But before I knew it, I had bought a small camper van, loaded it with pencils and sketchbooks and had a summer of drawing stretching out before me.

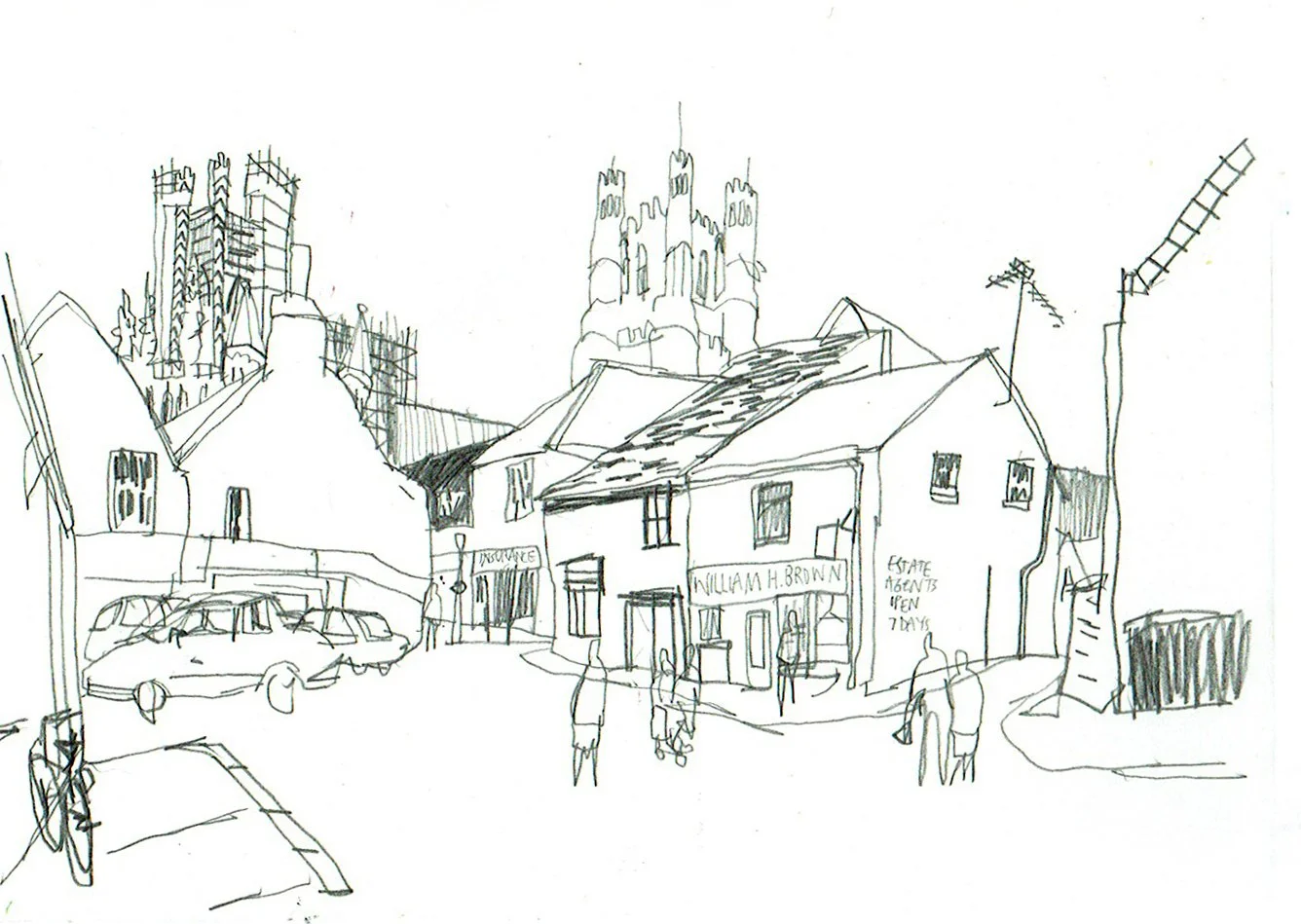

Ely, Cambridgeshire

As it turned out, almost everywhere had its surprises. It came as a shock to find some places exactly as he had described them, just as it was to find others so changed. But it was those unlikely events that popped up out of nowhere down country lanes looking for somewhere to park overnight that I enjoyed most, the people ready to invite you into their homes or help push the van. They were the things you could never plan. The English people don'’t seem nearly as wary of strangers as we are led to believe.

But it made me aware, too, of just how much colour and history there is a short drive up the least likely roads. We rush to the international airports with only the haziest idea of what is just over the hedge. What is closest to home is so often what is most overlooked.

We are regularly spoon-fed the heritage trail hype, shepherded about as if we are incapable of original thought, depriving us of any sense of discovery. Perhaps that is the natural conclusion of what Morton was encouraging in his book. But if you have the time to slow down and stay off the motorways and dual-carriageways and see what you can find, there are many more rewards. England is a compact island and it never fails to respond to the slow, patient search.

With that in mind it was at times frustrating restricting myself to follow Morton's route. We were hardly ideal travelling companions. There were times when I would have happily thrown his book out of the van window and struck out on my own way. There were roads off his tracks that I found impossible not to take, and few were disappointing when I did.

Ultimately, however, I remained faithful to Morton and his book and I suppose I'm glad of that. Had I not remained faithful I would probably still be out there somewhere even now, driving the lanes looking for somewhere to camp or, more likely, waiting yet again for the RAC man to arrive.

James Hobbs, 1990